Czerwonka Versus Owens

Appendices, tangential information, and one man's views on the complex events surrounding the contest for the KY House 43rd District leading up to Election Day 2004. Michael Czerwonka vs. now state Rep. Darryl T. Owens.

Thursday, October 27, 2005

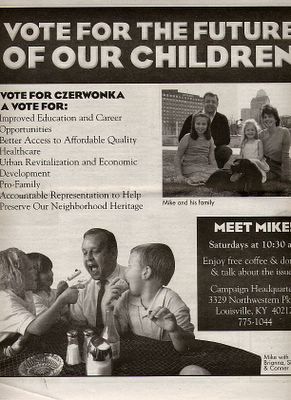

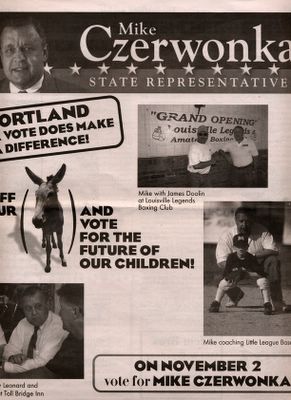

Right hand page of advertisement. Left side features complaints regarding Owens, and Czerwonka's qualifications. See previously posted scan of left leaf.

The Political 43rd: Effects of the District on the Candidates' Learning Curves

The candidates were asked whether their personal view of the 43rd district changed significantly after each of their first campaign experiences (Czerwonka in 2002, Owens in 2004). Mr. Czerwonka had a significant amount to say on this topic, comparing and contrasting his two unsuccessful campaigns for this seat. Mr. Owens generally did not feel that the campaign for this seat was a learning experience, so this section mainly discusses Czerwonka’s learning curve, from his perspective.

Czerwonka addressed how his perception of the 43rd district had changed after his first attempt at the seat in 2002, necessarily explaining some of his presuppositions along the way. One might conclude from his answers that there were presuppositions that seriously hurt him in both campaigns he ran, in 2002 and 2004. These assumptions ranged from beliefs about how the Republican Party should handle his race, to things he learned about the various subcultures amongst his prospective constituency.

The first area in which Mr. Czerwonka’s first campaign changed his perspective of his district was in relation to Republican Party activity. He had counted on the party to staff the precincts and to challenge attempts at voter fraud. “My views changed in that I realized that I could not rely on the local Republican Party to do their job of staffing the precincts in the most challenging of areas in Jefferson County with qualified Republicans.” Jefferson county had already developed a notoriety for electoral corruption before Czerwonka’s 2002 race against Paul Bather. He said that many votes were cast illegitimately against him in 2002, and so he knew to be prepared against these tactics in 2004. In 2003 he was selected to recruit and place challengers in every precinct’s polling place in the 43rd district, to stem the expected tide of electoral corruption during the 2003 Kentucky Gubernatorial race. By 2004, Czerwonka was much more prepared to deal with illegal vote-gathering techniques, fraudulent voters and polling-place electioneering. “This was something that know we had to do and we did it extremely well,” said Czerwonka of his 2004 campaign’s organizational efforts.

Having also had a chance to feel out popular response to former incumbent Paul Bather, Czerwonka understood that his close brush with victory in 2002 was not necessarily indicative of his own success with voters. He concluded rather that the incumbent Bather was so unpopular as to almost allow his opponent to surmount the insurmountable, which Czerwonka had almost done. “I knew exactly what the challenges were in the district,” said Czerwonka, referring his own white, Republican status in a 60% black, 90% Democrat district. “I also knew that no one sans Saddam Hussein or Osama Bin Laden generated as visceral of a response as Paul Bather, …that 2004 was…a Presidential Election Year, very hotly contested, [and] that my opponent for the General Election, Darryl Owens, was going to present a different type and style of campaign.”

Adducing from the political atmosphere in his district, and what he had learned about his potential constituency in his 2002 run, Czerwonka opened his heart up to voters in the 43rd concerning his conservative family values views. In 2002 he learned quickly that voters in his district, even those who did not have sound families for themselves, wanted that soundness of family values for their children, as well as better educational and career opportunities, and better neighborhoods. He knew that most of those in the black and white neighborhoods shared a churchgoing nature of some kind at least, and tended to be more socially conservative than most strongly Democrat constituencies would be. Therefore the Czerwonka camp considered seriously, as he stated it, “that in 2004 there was a Constitutional Amendment on the Ballot defining Marriage as between a man and a woman,” and that their chances of success were likely tied to the family-oriented sentiments of their toughest votes to win: the entrenched black vote. “…Knowing the fact that the poor, Christian blacks of West Louisville cherished their families, [we thought] hopefully those black families would analyze the candidates and realize,” he said, that he was on their side, and “that this was clearly an issue on which my opponent and I were diametrically opposed.”

Czerwonka’s approach, then, was one of assessing the issues carefully after his first campaign, and attempting to educate his constituency as he campaigned to win their trust. He approached the campaign in a fashion that comfortably reflected the things he thought he shared with the best parts of the district: a disciplined work ethic, exerting his efforts diligently on the ground to win trust voter-by-voter, one-by one. He also ensured that he was well informed as to the actual issues that the average voter in each subdivision of his district cared about, or should care about if they did not.

The Political 43rd: Aspects of the District as Political Motivators - Darryl T. Owens

Representative Owens spoke much less specifically or openly about his motivations in running for office. In response to the same question that Mr. Czerwonka answered at length, Rep. Owens’ response was typical of most of his answers: concise, and to the point. He did not put his district in such abstract nor actually such concrete terms as his opponent. In response to the question, “Were there specific aspects of this district that made you want to run,” Owens referred to his professional public service experience, and the ethnic and economic demographics of the constituency.

First Owens referred to his recent experience in what he considered a similar representative situation. This suggests a close mental connection between his former experiences with how he views his position now. “The district was similar to the district I represented as ‘C’ District Commissioner.” Jefferson County, Kentucky, is divided into three districts, lettered “A” through “C.” Owens originally won the “C” district seat in 1983. Though he failed to win his Mayoral bid in 1985, he went on to hold his seat representing Jefferson County “C” District for five terms, completing his last term in 2002. The “C” District encompasses the southwest third of the county. Since the Jefferson County/Louisville merger on January 6, 2003, the county government and Louisville City governments were all but dissolved and replaced by a new Louisville Metropolitan are government. Though the district positions were not going to be dissolved, the responsibilities and pay of the commissioners would be negligible as the positions were no longer needed. For this reason Owens left the position in 2002 and sought election in 2004 for the position he now holds.

“C” District, according to Owens, was made up of roughly two-thirds white and one third black voters, of widely varying income levels similar to the 4rrd Kentucky House District for which he was now running in his 2004 race. Having held this Commissioner position for twenty years, he felt that the ethnic and income diversity of the State House district, located in roughly the same region, more than qualified him to represent it in Frankfort.

The Political 43rd: Aspects of the District as Political Motivators - Mike Czerwonka

Asked what aspects of the district, when he first ran for the office in 2002, had influenced his decision to run, Czerwonka did not start by describing the district. He first explained himself, and then his district. His own belief in “honor, dignity, and integrity” and “taking risks when the risk is worthy,” combined with several other personal motivations, were the first allusions he made, before making any reference to aspects of the district itself.[4]

The factors motivating Czerwonka to enter the pursuit of the 43rd district seat included several aspects of the district itself. When asked if there were characteristics of the district that motivated him to run for office, Czerwonka’s response included references to four main concerns for the district. He took issue with (1) misrepresentation caused by a poorly redrawn district, (2) the character of incumbent Paul Bather, (3) his concern for the political disenfranchisement of those who could not fight for themselves, and (4) the atrocious state of the district, including corruption and poor educational standards.

(1) Misrepresentation. His frustration over lacking representation after the redistricting of the 43rd in 2001 almost propelled him to his own representative seat in Frankfort in 2002. The Democrat-controlled state House and the Republican state Senate had been at odds. According to Czerwonka, the House had concocted a redistricting plan that would, they had hoped, rid them of Rep. Paul Bather, while still allowing them to keep the 43rd seat. “…[The] Democratic controlled House of Representatives redrew the boundaries such to ultimately rid itself of the most morally reprehensible scumbag that has ever been elected to public office in Kentucky, Paul Bather.”[5] The Senate, not wishing to call opposition onto their agenda, had not challenged the gerrymandering scheme. Supposedly, the resultant redistricting had been meant to displace Bather by combining starkly contrasting constituencies who would not support a black, centrist, former Washington, D.C. Republican turned conservative Democrat. In the process, the conservative parts of the district were left bereft of any real representation, stranded in a district where they were held as a part of a permanent, artificial minority vote.

(2) Paul Bather’s Character. Not to say that Czerwonka thought Bather was worth keeping. Czerwonka would later refer to him in very colorful language, including, “morally reprehensible scumbag.”[6] He would have been just as motivated to replace Bather if the redrawn 43rd had never come about. Summarily, he disagreed with Bather and equally disagreed with the misrepresentation resultant from the Democratic efforts to displace Bather.

(3) Political Disenfranchisement of the Helpless. Czerwonka’s reasoning implies a complete inability on his part to separate political corruption from its indirect, intangible effect on the children of the district. From his first answer to his first question, he interpolated that a representative “should be someone that you [would] be proud to introduce to your children.”[7] He points out that the extraordinary gerrymandering resulting in the 43rd district, the inordinately high electoral corruption there, and the controversy surrounding his own efforts to put poll watchers in every precinct there were all inordinately flagrant corruption stories. Each of these stories made national news despite being very localized, small-time problems at first glance. In Czerwonka’s eyes, that makes his district one of the most notoriously poorly represented collections of neighborhoods in the U.S. Considering that this country, he reasons, supposedly guarantees representation to its people by right, there is no difference between raising children in a corrupt electoral environment and directly robbing Louisville children of their rights.

(4) Corruption, Education, and General Disarray. Regardless of the children, the history of the district, especially its reputation for corruption, was a recurring theme in Czerwonka’s discussion of his political motivations. He spoke in terms of his district’s political demography, to highlight that in 2002 political affiliation was not the important distinction to this constituency. He then explained the closeness of that race, expressing the margin of his defeat in votes received. “Even though we were out-registered 4-1 (Democrats vs. Republicans) in party registration in the 43rd LD, we only lost by 695 votes out of 10,000 total votes cast.”[8] More to the point, he cited the number of votes he perceived to be fraudulently received:

It was during the 2002 election that the Jefferson County Republican Party failed to place Precinct Poll Workers in 53 individual precinct positions. Most of the vacancies were in West Louisville and Portland, an area of the county that was a significant part of our district. We had over 25 calls of voter fraud on Election Day 2002. Upon investigation by the FBI it was determined that in only 1 of the 13 precincts that they investigated did the number of ballots cast match the signatures in the voter registration books. They also mentioned that they were able to identify where men signed the registration books next to women’s names.[9]

But Czerwonka also cited tangible concerns for the kids in his district. Still discussing his reasons for his first run in 2002, he used one of his favorite phrases to describe his modus operandi: “I also believe that when confronted with this type of [corruption]…you must be willing to fight the battles on behalf of those who can’t fight them for themselves, primarily the children.”[10] What he means by this is that the children of the district suffer directly in very practical, concrete ways. From the high violence rates, to the low education standards, to the degradation of living conditions in the poor parts of the district, Czerwonka believes that the youngest residents of the 43rd suffer the most at the hands of his political opponents.

[4] First Czerwonka Survey, Page 1. Available at URL: http://gabe.250free.com/DiscoveryQuestions1_Czerwonka_Answers.pdf

[5] First Czerwonka Survey, Page 1.

[6] First Czerwonka Survey, Page 1.

[7] First Czerwonka Survey, Page 1.

[8] First Czerwonka Survey, Page 1.

[9] First Czerwonka Survey, Page 1.

[10] First Czerwonka Survey, Page 1.

The Political 43rd District

The first step in understanding a campaign is to understand the district, and to use the district to understand the candidates, and vice versa. The candidates’ view of his district will at least indirectly determine whether and why he becomes a candidate. It will shape his beliefs about his chances of success in the race, and thus will determine in no small part the strategies adopted for the campaign, and the methods used to carry out these strategies. We will explore points of view of both Mr. Czerwonka and the incumbent Mr. Owens, in their own words about the district, and use that information to better understand the circumstances that followed and the results on Election Day. Both Owens and Czerwonka’s responses followed a line of thought that compared themselves favorably with their prospective constituency.

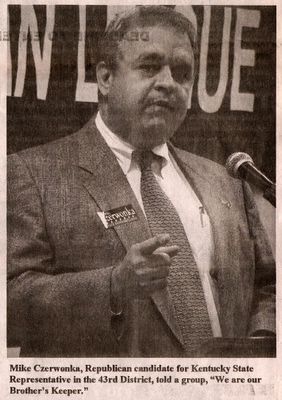

Full text: "Civil Rights Activist Mattie Jones Joins Mike Czerwonka's Campaign for State Representative." Louisville Defender, September 30, 2004. Page A8

Related Newspaper Scans

Print Head Mike Czerwonka J.C. Watts

Czerwonka Supporters Mattie Jones

Introduction: Part III - District 43 of the Kentucky State House of Representatives

As a designated diversity district, the 43rd, has necessarily suffered identity crises because it contains strongly contrasting demographic groups. The neighborhoods to the North and West, encompassing boat-dwellers and sundry miles inland from the riverbanks, between Chickasaw park, through the pseudo-ghettos west of the downtown blocks, along Interstate 64 and River Road east as far as Lime Kiln Road, constitute the 43rd. It is, by some estimates, home to the poorest and richest neighborhoods in the United States.

While advanced electronic devices, split-second communications networking, and the latest newfangled campaign tools typify the average campaign in a west or east coast state, this part of Louisville is closer to its cultural, historical roots. It is also tangled in political wrangling and special interest, deeply inlaid down to the foundations of local politics. A river port town, also driven by struggling horse-racing and manufacturing sectors, Louisville has been forced to struggle. No parts of town have been more heavily affected than the 43rd, which includes the aptly named Portland township and the now ghostly industrial district west of the downtown area. As jobs have become scarce, welfare homes have become abundant, and a once thriving working community has reduced men of all colors into a remnant workforce that provides little more than a shadow of more successful times past. In the 43rd District, which will be the base for political analysis in this paper, campaigns do not open shop until ten or eleven o’clock in the morning, even in the heat of mid-October electioneering. Why? Simply, it is pointless to campaign to voters who are not up to talking about politics, because they are not even up out of bed. Thus the unemployment rates and welfare slums affect the most practical aspects of politics.

Residents of Portland, a 43rd District neighborhood that used to be an independent township, still clutch to older, better days. They will happily tell you what a nice neighborhood it was before federal Section 8 housing began hurting local property values and causing home ownership to fall. Missing a few teeth, nervously tapping a cigarette, an elderly Portland local may well tell you about the old days in a tone that shows she has long acknowledged that the good parts about those days are long gone. Mixed with her drawled, “Oh, yes, honey, this town used to be a fine place indeedy!” comes a regular cursing stream of verbalized worries about health care premiums, public aid checks, town meetings, and unstable, low-paying jobs. These are not complaints: they are real problems this campaign volunteer cannot ignore, that she hopes her candidate will be able to finally address.

In the deep west end of Louisville one finds the Black neighborhoods, which boast a rich cultural difference from the predominantly white Portland area. In some cases the two boroughs lay literally across the street from each other, but are wholly separate and distinct. This bright line that divides the birthplace of Muhammad Ali and the old shipping town only separates two of the three distinct subsections of the district. As though the 43rd were an animal with a tail, there is reaching out from the relatively square western side of the district a suspiciously narrow appendage along the river, which encompasses the extremely well-to-do River Road residential district, complete with lavish boathouses and tobacco and whiskey manors and land holdings. As though the ethnic contrast between the poorer Portland and West side were not enough to amuse the political whims of redistricting Frankfurt politicians, this River Road subsection lies in arrant dissimilitude in its astronomically higher average income bracket.

In 2004 a peculiar and unique political battle took place in the 43rd, spurred on by an open Representative seat in the state House in the Frankfurt state capitol. Mr. Michael Czerwonka, an experienced candidate, ran the Republican ticket against Mr. Darryl T. Owens, a Democrat, seasoned local bureaucrat and retired former President of the Louisville National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The purpose of this paper is to document this electoral race and learn from it whatever possible about the district, the state, and electoral political science in general. The goal of the author is to speculate on the reasons for the outcome of the election, possible alternative outcomes had one or both candidates done things differently, and what would have been required for a much more remarkable though not so distant reversal of the results.

The majority of the research used in this paper will not be cited material from published sources. The race in question was a relatively small one; while Czerwonka and former state Representative Paul Bather made national news, each in his own right, in 2002 and 2003, this race is was just as fascinating but not considered as newsworthy. Instead research backing this paper is supplemented by original answers by the candidates and others who were intimately involved in the campaign. The questionnaires used to gather this information were based on (a) concepts of home-style politics laid out in the definitive work on the subject by Richard F. Fenno, Jr., and (b) responses made to earlier questionnaires.

Wednesday, October 26, 2005

Introduction: Part II - The Louisville Metro Area

Along the Ohio River bank, opposite Indiana, is Kentucky's largest populous area: the sprawling Metropolitan of Louisville. Through any lens, Louisville is a visually fascinating town. It has a brick-and-stack industrial flavor to its architectural landscape. This is moderated by an intangible refinement, most likely lent by the influence of the monster whiskey and tobacco interests based thereabouts. Louisville has made great efforts to catch momentum from the technology surge of the last fifteen years, though getting a late start, and is becoming a good place to be “wired.” In fact, Louisville is one of the pioneering metro areas for at least one rapid-growth industry in health care:

The Louisville Medical Center, a 20-block area in Downtown Louisville, houses some of the world's most pioneering doctors and is a thriving business park. But, outside the center, the industry still plays a large role in the community. Two Fortune 500 health-related companies are headquartered locally. And Greater Louisville is home to 15 hospitals and thousands of quality medical professionals. About 72,000 employees work for the more than 2,000 health-related companies - which include health care providers, medical supply companies, insurers and claims processors. The employees earn more than $2.4 billion annually. [1]

Through a microscope, as it were, the political science student finds a veritable archaeological dig in Louisville. Scratching, gently chiseling and brushing through layer after layer of collected influences that no longer hold such sway in other such metropolises, our political scientist will find himself dealing with a much more sophisticated politick than first let on by Kentucky’s façade of red-necked simplicity. The scene of several local and state government campaign contribution fraud and laundering scandals, Louisville could also be the poster-child region of the poll-watching controversies of the last few election cycles nationally.

Additionally, Louisville is the home of one of the most newsworthy policy innovations in American local government. It recently merged its constantly chafing Louisville city and Jefferson County government bodies, dissolving their structures and replacing them with one Louisville Metropolitan Area authority. The merger was controversial,[2] but it was chosen by area voters and has been largely successful, leading other metropolitan areas such as Pittsburgh to suggest that the same solution might work for them.[3]

In the same matrix of innovation, growth and change, there can be found some of the oldest lingering scars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries of American politics. The city is still divided into recognizably different, ethnically distinguished subsections, separating the sequestered Black communities from the starkly contrasting poor and rich white neighborhoods. The lingeringly apologetic Civil War politics of greater Kentucky fall heavily on the shoulders of the otherwise forward-straining Louisville area: it is the home of the 43rd District of the Kentucky Commonwealth’s House of Representatives, which has been designated by the majority Democrat party as a racially-designated Black district. Where many other states do not even remember the ghost pains of Civil War wounds, Louisville is discontent to merely enjoy its hard-won diversity; it rather painstakingly mandates and maintains it.

[1] Greater Louisville, Incorporated: The Metro Chamber Of Commerce, “Health Enterprises.” GLI Website, available at URL: http://www.greaterlouisville.com/content/community/health.asp. Accessed 5 May, 2005.

[2] Shafer, Sheldon S., “Louisville Gladly Becomes Model for Merger.” The Louisville Courier-Journal, 2 January 2004. Available at URL: http://66.102.7.104/search?q=cache:KR2Ns21_sIUJ:vh80015.vh8.infi.net/localnews/2004/01/02ky/met-front-bandwagon0102-6766.html+%22Courier+Journal%22+darryl+owens&hl=en

[3] Bill Toland, “Louisville becomes lean, less mean after city/county merger.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 7 September 2003. Available at URL: http://www.post-gazette.com/localnews/20030907louisville0907p3.asp. Accessed 5 May, 2005

Introduction: Part I - An Outsider's Kentucky

Kentucky lies at the heart of America. While it is not literally the center of the map, if you are familiar with the socio-political landscape of the nation you probably understand the expression. Kentucky is lynchpin to most of the regions in the continental American geographical vernacular: it borders Northern states West Virginia and Ohio, Southern states Tennessee and Virginia; and Midwestern states Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana. It constitutes the northern strip of the Bible belt, and borders the southern edge of the rust belt. Innervated with cultural and ethnic roots, Kentucky connects America to her politically lucrative history. In many coastal states, information-age ethnic mixing reduces race tensions to a trite political card game—and a veritable thing of the past—as “whites” are gradually introduced to minority status. Meanwhile, Kentucky still struggles with racial divides predating the Civil War.

The population still retains a stereotypical, twentieth-century American ethnic makeup: Caucasian by majority, with an irrepressible African American minority. But the proverbial “melting pot,” which has continually made America important to so many immigrant families for centuries, is not wholly absent. Kentucky boasts small Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Middle Eastern populations to accent the traditional Black/White divide. Still, the divide remains. The NAACP is strong in Kentucky’s metropolitan politics. Shining black gospel churches dot the street corners of a quarter of the largest city, Louisville, adding a kind of hopeful solemnity to a landscape of quickie marts, boarded up buildings, and cyclone fencing. They are as conspicuously absent in the other three quarters of town as “white” churches are in the “black” quarter. Westerners characterize those who live in the east end of the state as poor white trash. But in the city, poor districts are comprised of predominantly black, low-income, welfare ghettos, which elect Black representatives—when district boundaries can be arranged—to represent the African-American community’s interests. Louisville and Lexington, the two most nationally recognizable metropolitan areas, both have homicide rates that rise well higher than many other similar cities. The locals will tell you many of these deaths were the result of regressive racial tensions. If you visit the side of town where skin colors change, you might believe them.

Amidst the crumbling old industrialism, such as can be seen boarded up near Bank Street and Rowan in Louisville, there arise the tender shoots of new, flourishing economic direction. Small pockets of technological economic growth provide contrast against old-fashioned rural, manufacturing, gambling and coal mining regions. The old economy is still predominant. But it is shrinking, much to the chagrin of the labor men and many workers who had still counted on old-world retirement plans, complete with guaranteed, “company-man” 401k securities. Workers in more advanced states increasingly rely on savings plans, transferable securities, résumés, and short-term-contracts, while these workers still hold to the tradition of relying upon the company for financial security. Kentucky has some of the richest and poorest neighborhoods in the United States. If you are interested in horse racing, use UPS shipping, smoke cigarettes, drink Bourbon whiskey, or simply use energy in your home, your consumerism is directly impacted by the Kentucky economy. Politically, there are progressive-thinking liberal voters and steady, business-oriented conservatives, old-order Blue Dog Democrats and Neo Con, pro-government Republicans. Almost everyone is supports Federal aid for local projects; but to be anti-gun is politically fatal for any politician. Many are against welfare but favor business or agricultural supports, or vice versa. On social issues, being pro-choice or pro-gay is probably not a good idea for those wanting to win and hold office. But if you’re pro-church, and support the traditional family model, you are a lock for election—unless you’re a Republican. Then campaign staffs might be forced to fight an uphill battle to convince old-order Democrat families to “re-think” their persuasions; parties may change, but tradition dies hard.

Culturally, Kentucky is not quite mid-western, nor actually southern. It bears many of the marks of both regions, so that it is often compared with West Virginia, a Yankee state by historical definition, but southern in many cultural and political aspects. Wedged between the liberal agenda of the labor unions the workers rely on as their last hope, and the conservative Judeo-Christian values of the Bible belt region and the south in general, the rust-belt Kentucky atmosphere is one of political upheaval in these changing economic times. A most confusing state to an outsider, Kentucky is as striated and divided within as it is separated from the states around it by lack of association. Kentuckians have a drawl that sounds southern, but are as connected to the northern states of Ohio, Illinois and Indiana as they are to Tennessee and Missouri. Ask the locals: some will say they certainly are a southern state; the rest will just as firmly assure you that they are not.

Editorial commentary welcome.

Thank you, the Author.

Wikipedia: Mike Czerwonka

Here is my initial entry on Mike Czerwonka in Wikipedia. An Owens article will follow.

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Academic Paper External Link

Here's is a link to an early section of the paper, when I expected it to be about thirty pages and no longer. Of course, it grew since then. I believe this section remains almost wholly intact.

Author's Note: Blog Purpose